My Name is Mayo

"Each atom of that mayonnaise, each mineral flake of that night filled jar, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man's heart. One must imagine the player happy."

To many players, 2016’s My Name is Mayo is a simple game. You tap on a jar of mayonnaise and unlock trophies. Some cynics may see it as a simplistic clicker game, one that offers a single mechanic that barely qualifies it as a game at all. Others may see it as a simple avenue for players to acquire a platinum trophy on the PS4 for 99 cents and less than an hour of play time. All of those cynics may have a point, but only on the surface.

A deeper look at My Name is Mayo reveals a grueling trial that holds a mirror to modern life, revealing all of the absurdity that defines labor in a contemporary service economy. With each tap of the mayonnaise jar, you come closer to truly understanding your own alienation, and with each trophy unlocked, you regain a small sliver of meaning, if only for a moment.

The entirety of My Name is Mayo revolves around a single image: a jar of mayonnaise that must be tapped. There are no load screens for new levels, no introductions of side characters, no cinematics to handle world-building and character development between action set-pieces. The image of mayonnaise is all you see, and tap on it is all you’re asked to do.

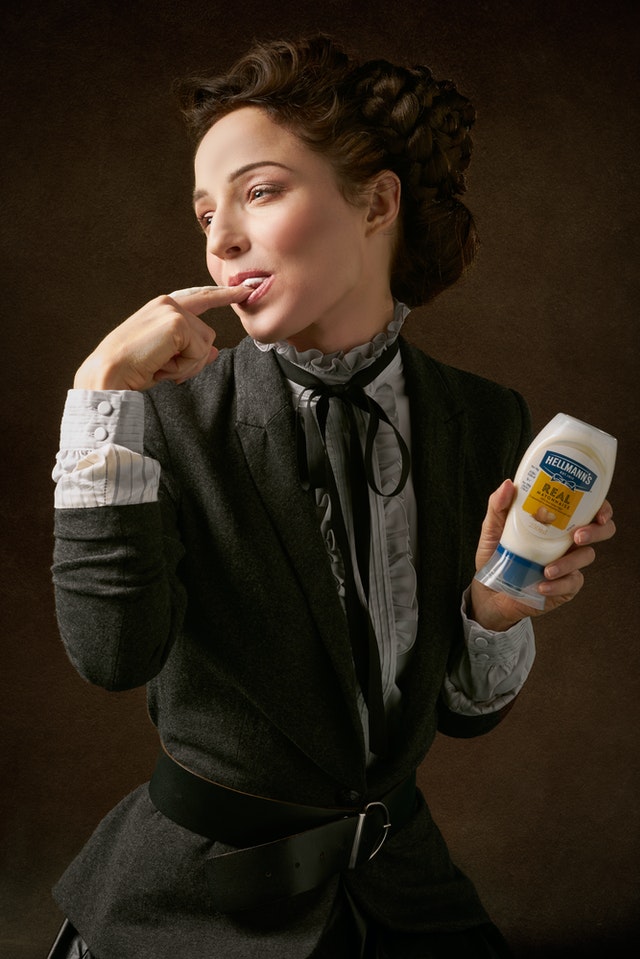

While the aesthetics of the jar periodically change — at times, it might don a leopard print bikini or some other comical article of clothing — the jar itself is always the core underneath. It remains an unremarkable consumer product, like one might find on the shelves of any supermarket. That mundanity may have been a design choice one might categorize as "so random," but on the other hand, it also may have tapped into the aesthetics of branding and packaging that signify variety on a store shelf despite the near-identical properties of the products themselves. It may have exposed the illusion of choice that haunts us all, along with the moments where that illusion slips, a near-universal experience every player has likely had while staring at a supermarket shelf like that guy in The Hurt Locker.

The central image also may have been a reference to the 1995 episode of Rocko’s Modern Life titled “Wacky Delly.” Throughout the episode, Ralph Bighead attempts to sabotage his contractual obligations by creating a purposefully terrible TV show, at one point airing an episode which consists of nothing but a static shot of a jar of mayonnaise for the entire runtime. He makes no commentary on the jar, but instead lets the image speak for itself, inadvertently resulting in even greater popularity for the show. As a child viewing that episode, I found it to be a harbinger of things to come — the inevitability of burnout, and the coercion of labor under capitalist modes of production — but I also thought it was funny because it was "so random," and probably because I had already internalized some hackneyed Gen X attitudes about modern art.

"Sometimes the jar of mayonnaise is wearing a bikini. Other times, it might be wearing a wig and holding a guitar. This is what cultural anthropologists refer to as 'so random.'"

In both of these cases — My Name is Mayo and Rocko’s Modern Life — the image of a jar of mayonnaise feels not like an arbitrary choice, but like a stark representation of contemporary consumer culture. It appears silent and unmoving, and in so doing, captures the bleak detachment of capitalism. The mayonnaise holds a mirror to the emptiness in all of us.

That emptiness doesn’t come from imagery alone, though. An essential part of My Name is Mayo’s impact is its single gameplay mechanic: tapping on the jar. The game pushes the player to tap, but doesn’t provide any real instruction as to the purpose of tapping. Without a clear goal, and with no real attachment to or understanding of the product of the action, the player becomes separated from their labor. At times during play, I even found myself looking at my phone — reading the insights of great intellectuals on Twitter, of course — while absent-mindedly continuing to tap on the jar, my actions automatic by that point.

Some may see the single mechanic as a bare-bones way of stream-lining interaction in a game that provides nearly none. Ultimately, that may be true. As the game progresses, you begin to wonder whether or not you may be damaging your controller by pressing the same button so much. You wonder whether you may be giving yourself some kind of repetitive stress injury. Time moves slowly, and you think back to other games you’ve had similar interactions with — perhaps you’ve clicked a large cookie at some point, or helped some kittens survive in a forest — but you recognize that those games offered a kind of narrative immersion and worldview that My Name is Mayo does not. You wonder why you’re doing this.

"I am still tapping the jar of mayonnaise to this day. My bones will turn to dust before I stop. I am become mayonnaise."

Like Sisyphus, you press on. As you struggle, the game begins to reframe your understanding of life. You imagine yourself at work, a wage slave exploited for the value you create, and feel yourself becoming more and more alienated from both the product of your labor and the act of laboring. You imagine yourself tapping at your desk, or at your cash register, wherever it may be. Every email becomes mayonnaise, every customer, mayonnaise. You tap and you tap, not because you want to, but because survival demands it, because if you stop tapping even for a moment, you won’t receive that paycheck marked with a paltry sum and your name, a name you’ve come to loathe, a name you barely recognize as your own.

The future looks bleak as you realize that the game is little more than its mechanics, and its mechanics are struggle. Tapping comes to represent the futility you feel every day, the absolute desperation that overcomes you each morning during your commute as you try to imagine an endpoint where you’re freed from the coerced tedium of wage labor. With every tap, you instead settle deeper into a quiet acceptance of the fact that only physical and mental decay will free you. You think of your co-workers, your friends, your family — everyone you’ve ever known or loved — and realize that nothing will free us collectively from these conditions.

All of us are Sisyphus. All of us are Ralph Bighead. All of us are trapped.

Through achievements, however, My Name is Mayo offers absolution. After only five taps, your first achievement pops up on the screen. Should you embrace it, you’ll immediately feel a surge of dopamine healing your callused, ruined brain. Similar things might happen to you as a wage laborer as well — maybe a pat on the back from the boss, or some kind of thank-you note that comes with a 15 dollar gift certificate to TGI Fridays — but a key difference makes the game achievements meaningful in a way that no other labor can match: they’re finite.

With every achievement, you know you’re coming closer to acquiring all of them. Earning every achievement isn’t technically an endpoint to the game — you can keep tapping that jar of mayonnaise for as long as you want — but it provides the illusion of an endpoint, and the illusion is enough. Just as the tragedy of Sisyphus stems from his consciousness, which makes him aware and emotionally connected to his own struggle, so too does the awareness of illusory achievements allow you to derive value from your labor.

By embracing achievements as a personal source of meaning, you can become an absurd hero in your own right. You can embark on a journey not simply of struggle, but one that recognizes your progress, that announces your accomplishments through on-screen notifications and allows you to alleviate your alienation. Your labor becomes your own, and even though the reality of capitalist coercion still dictates your actions in day-to-day life, you know that at some point — even if it is only for 45 minutes or so, even if it destroys your controller and all the connective tissue in your thumb, even if it crashes when you try to look at the leaderboard — you have achieved. Like Sisyphus, your fate belongs to you.

"PS4 trophies are quickly replacing ketamine as the promising new treatment for major depression."

When the oceans have dried, when the forests have all burned away, when you’ve moved inland from the rapidly flooding coasts in search of safety and can only find work as a part-time Rearden Steelworker at whatever private militarized enclave still exists, you’ll remember what you accomplished. Years of labor at your various jobs earned you nothing but a wage — somebody else’s work for somebody else’s product — but just 45 minutes of tapping earned something with true meaning, something timeless, something that marks an endpoint. Just 10,000 taps and My Name is Mayo gives you what you truly need: a platinum trophy.

Or a bunch of XBOX points, or whatever. I don’t know how that works.