Yakuza 4 and the Brand New Perverts

June 17th, 2022

Unlike previous entries in the Yakuza series, Yakuza 4 offers up four playable protagonists, each with their own distinct combat styles and storylines. It was an ambitious change, and interesting in a lot of ways, both in terms of gameplay and narrative. That said, the addition of new protagonists also led to it being the first game in the Yakuza series to leave me with some real skepticism and frustration about its primary characters, largely because of the ways characterizations intersect with the red-light district of Kamurocho.

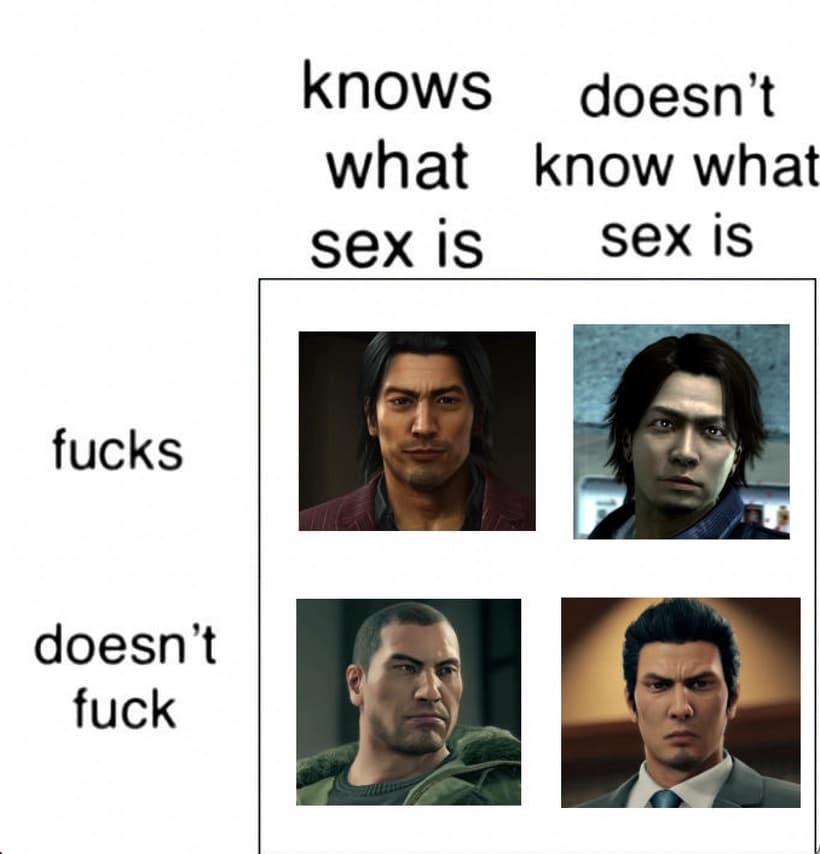

Ultimately, the central thesis here looks a little like this:

Before we get into any of the new characters, let’s look at the central protagonist, Kiryu, and his role in the series as a whole.

Kiryu: The Baseline

A central part of the charm of the Yakuza series is the fact that Kiryu respects everybody. He’s powerful to an often absurd degree, like when people punch him in cutscenes and he just chooses through sheer force of will to not get hurt, and he’s a near-mythic figure in the history of the Tojo clan, which would prevent young toughs from doing random encounters to him on the street if he wasn’t too humble to boast about his status. Despite all that power, he’s absolutely incapable of abusing it. The man is positively shackled by honor and earnestness, and he treats everybody he meets as fundamentally equal to himself.

It’s exactly that characterization that makes a lot of things about the games palatable where they otherwise might not be. For example, one of the reasons I initially ignored the Yakuza series was because I assumed it would be something along the lines of GTA in tone: a mean-spirited crime romp where you joyfully hurt people and take in a “we make fun of everybody equally” South Park-style sense of humor that reeks of misanthropic nihilism. A game like that, mixed with the often fairly explicit forays into the Kamurocho sex industry that the Yakuza games offer, would probably be a nightmare.

With Kiryu at the helm, it loses a lot of the hard edges, because it’s difficult to view Kiryu as somebody who would ever knowingly exploit anybody. He takes everybody seriously, no matter how absurd or zany their stories might be. When people talk to him, he’s interested in what they have to say. If he wrongs somebody, it’s either inadvertent, or something his strict code of honor absolutely requires that he do. He’s not meant to capture gritty realism, or even basic verisimilitude, but comically aspirational heroism.

Unfortunately, Kiryu is not the only protagonist in Yakuza 4.

Akiyama: The Guy Who Knows and Does

The game opens on a new protagonist, Akiyama. That’s jarring in and of itself, given that the previous three games have been nothing but nonstop Kiryu looking at stuff and saying “nani?” in his monotone voice, but he’s not so bad. They seem to want you to think he’s cool Kiryu, because he (at first glance, at least) isn’t as hampered as Kiryu by the incredible weight of honor. He throws money around like it’s nothing. When he talks to girls at cabaret clubs, he doesn’t seem confused by what’s happening. He’s slick.

That also means that he doesn’t radiate empathy and respect the way Kiryu does. When he interacts with any of the sex industry aspects of Kamurocho, it doesn’t quite feel safe the way it does when Kiryu does the same things. When he plays ping pong with a nice young lady at the onsen and it looks like her robe might fly open, it feels a little weird, because the Akiyama we know is somebody who might leer at her. He might say something gross, or flirt with her. He might pursue her.

A gentleman gamer having a respectful time with Female Guest

Kiryu, on the other hand, consistently feels like a person who would not leer. That’s often what makes it funny for Kiryu to be in those kinds of situations: his almost child-like naiveté. Even if the girl at the onsen exposed herself on purpose to flirt with him, he wouldn’t get it. He would look at her and grunt, stone-faced and respectful. He’s incapable of being a creep, because he doesn’t have sex, and he doesn’t know what sex is.

Akiyama, I feel certain, does both.

Saejima: The Brick Wall

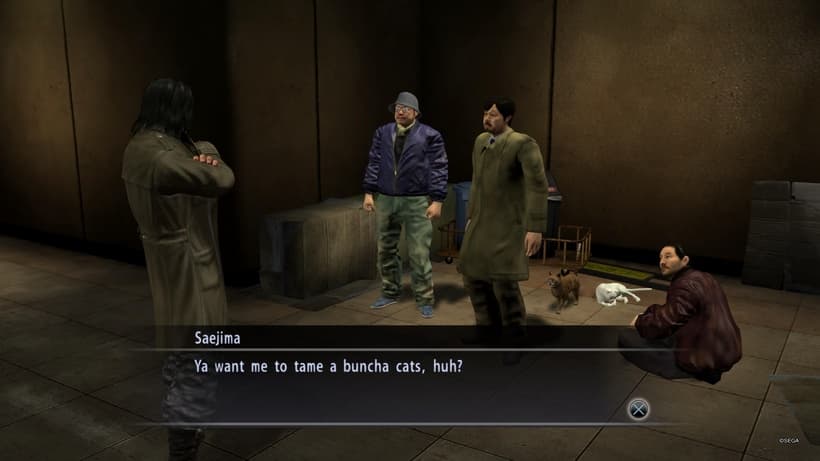

The next protagonist is Saejima, a man with almost as much honor and self-discipline as Kiryu. For the most part, he functions very similarly, because from his introduction it’s made clear that his worldview, his moral compass, and his sense of duty are absolute and unshakeable. He’s a brick wall of a person, both physically and in terms of characterization.

That said, there’s one moment in the game, shortly after Saejima’s escape from prison, that undercuts it all. He washes up on the shore outside Kiryu’s Morning Glory orphanage – what an extraordinarily unlikely turn of events, but let’s just ignore that aspect of it – and is taken in and nursed back to health by Kiryu’s 14-year-old daughter figure, Haruka. Once he wakes up, Saejima sees Haruka there, and in a moment of weakness (I guess), pins her to the floor. It’s not made explicit exactly what he’s doing or thinking in that moment, but there’s a clear sexual element, the pent-up energy of a man just out after decades of prison, and even though he quickly leaves her alone, the violence of it is unmistakeable.

Saejima's general vibe at all times outside of The Haruka Incident

It’s only one moment, but it colors everything that follows. When Saejima interacts with the sex industry in Kamurocho, it’s hard to entirely trust him the way you do Kiryu. It gets easier, because that one moment feels so out of character, and by Yakuza 5 it feels nearly retconned out of existence, but still, it’s there. It establishes in no uncertain terms that Saejima knows what sex is. He abstains because, like Kiryu, he’s weighed down by honor, but that doesn't change that fundamental fact: he knows.

Tanimura: The Cop

The third protagonist is Tanimura, and he is, without a doubt, the worst protagonist in the Yakuza series. His primary failing is obvious: he’s a cop. Even outside of any explicit political reasoning there, it presents immediate narrative problems. The game has to expend energy getting you to believe that he’s not like the other cops, because if you played a character who walks around following the letter of the law in a Yakuza game, that would be boring. He has to skirt the law and do edgy stuff for the gameplay to remain fun and consistent, and for it to make any sense. He’s a cool cop who plays by his own rules.

Unfortunately, a cool cop who plays by his own rules in the Yakuza world looks a lot like a corrupt cop. The game tries to counteract this by giving him an honorable and sympathetic reason for acting that way – uncovering the mystery of his beloved father’s death – but it doesn’t do much to offset the bad taste playing this kind of character leaves. Every act of random encounter violence has a different feel to it than it does with any of the other protagonists, because he’s not of their world. There’s a social power imbalance there, and almost everything Tanimura does feels like an abuse of that power.

Tanimura saying some garbage that is unequivocally false

That comes into play more than anywhere else when he interacts with the sex industry elements. I initially expected that the game wouldn’t allow it, and that if you entered a place like the massage parlor while playing as Tanimura, there’d be a bit of self-talk about how he shouldn’t be doing things like that. There’s no distinction made, though, and no reference to Tanimura’s occupation, or the questionable legality of these “gray zones,” as Like a Dragon’s Bleach Japan refers to them. Tanimura does these things with no consideration.

In turn, you get a character who feels like he’s supposed to be something along the lines of Akiyama – a cool guy who isn’t saddled by being a perfect little angel all the time like Kiryu – but in Tanimura, there’s a certain thoughtlessness that even Akiyama doesn’t present. Like Akiyama, you get the distinct feeling that he does have sex, but unlike Akiyama, he doesn’t think about it, doesn’t give it proper consideration, and doesn’t understand the obvious implications his position of power brings to it. Maybe he's aware of sex in literal terms, but does he understand it? Clearly not, and in that sense, I think it's both reasonable and logically unassailable to say he does not know what sex is.

Back to Kiryu: The Virgin Father

Finally, we arrive at Kiryu, for real this time. He’s the last protagonist in the game, and when you return to him near the end, you feel palpable relief. It’s like standing on solid ground again after being lost at sea, or having heat actions actually work in a coherent way in Yakuza 5 after spending many hours struggling with Yakuza 3 and 4. He’s wearing his tropical shirt. He looks stupid. It’s great.

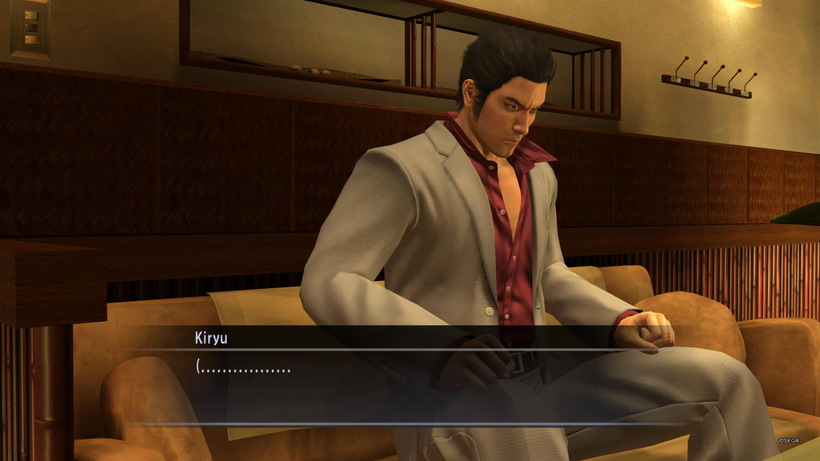

Kiryu's thought process when confronted with the concept of sex

When Kiryu goes to the massage parlor, the absurd minigame and various euphemisms feel funny and light-hearted more than anything else, because you don’t really feel like Kiryu is actually doing anything behind them. You can fully buy into the absurdity in a way that the other protagonists make more difficult. No matter what kind of euphemistically sexual activity Kiryu participates in, he makes it feel distinctly sexless, and in turn eliminates most of the off-putting power dynamics his own role as a tough yakuza guy bring to the table.

Kiryu’s consistent sexlessness is only enhanced by the fact that he’s literally surrounded by children – an orphanage full of them – as well as a daughter figure he has all but adopted as his own, and done it all without a partner. Somehow this man who both does not know what sex is and has also never had sex has become father to an ever-expanding roster of children. It’s the closest thing to a virgin birth one could do without a literal birth.

In Conclusion

At the start of the game, I wasn’t a fan of Akiyama, but he grew on me, and Saejima was much easier to get used to, especially once you forced the Haruka incident from your memory. Kiryu, on the other hand, takes no effort to love. It comes naturally, and with every monotone grunt, honor-bound choice, and staunch refusal to even be particularly hurt by what should be life-threatening injuries, he only gets easier to love.

All of this is to make a single, comprehensive point about Yakuza 4: Tanimura is the worst.

If you like this kind of thing and want to see more of it, or if you want to support the development of any current or upcoming games, please consider subscribing on Patreon.